Abbreviations

- LFLG – Low Flow-Low Gradient

- LVH – Left Ventricular Hypertrophy

- TTE – Trans-Thoracic Echocardiography

- AVA – Aortic Valve Area

- BNP – Beta-Natriuretic Peptide

- ULN – Upper Limit of Normal

- TAVI – Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation

- TAVR – Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (preferred over TAVI)

- SAVR – Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a common valvular condition that can have major hemodynamic consequences from the progressively stenotic aortic valve.

Types of Aortic Stenosis:

- Supravalvular (rare)

- Subaortic ridge or hypoplasia resulting in narrowing above the valve

- Valvular (most common)

- This category is the focus of this review

- Subvalvular (rare)

- Thin membrane, fibromuscular ridge or tunnel stenosis.

Causes

Senile degenerative/calcific (most common)

Congenital (bicuspid or unicuspid aortic valve)

Rheumatic AS (typically with coexisting mitral stenosis)

Other:

Prosthetic valve AS (not discussed in this summary)

Subvalvular and supravalvular AS (not discussed in this summary)

Pathophysiology

- The aortic valve can be prone to progressive calcification and stenosis, with similar risk factors as atherosclerosis such as age and hypertension.

- Some conditions, such as a bicuspid aortic valve, predispose a patient to earlier development of stenosis.

- Aortic stenosis results in a pressure-overload state in the left ventricle, resulting in LVH and diastolic dysfunction.

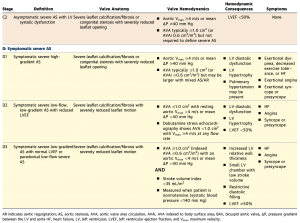

- The natural history of AS suggests a long asymptomatic “latent” period. Once symptoms develop, prognosis is very poor.

Diagnosis

History

The classical symptoms of severe aortic stenosis are:

- Angina: average survival 5 years

- Syncope: average survival 3 years

- Heart failure: average survival 2 years

Other clinical features:

Dyspnea due to diastolic dysfunction or eventual heart failure

GI bleeding due to angiodysplasia (Heyde’s syndrome)

High-velocity flow across the stenotic aortic valve leads to increased shear stress of blood cells, with resultant acquired von Willebrand factor deficiency

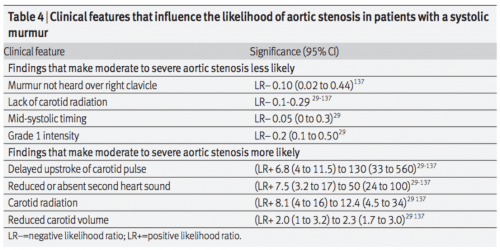

Physical exam

Vital Signs: hypertension in the elderly (risk factor)

Peripheral pulses:

Carotid artery: pulsus parvus et tardus (slow rising impulse with low amplitude), carotid thrill

Apical-carotid delay

Brachioradial delay

Presence of a precordial thrill

Auscultation:

Single or inaudible S2 (loss of A2 component)

Soft valve closure due to restriction of leaflet motion

S4 may suggest LVH

Systolic crescendo-descrendo murmur: later peaking suggests more severe AS

Radiation to carotids in severe AS

Radiation to apex (“Gallavardin” phenomenon of high-pitched murmur)

Later peaking murmur suggests more severe AS

NOTE: Intensity of the murmur does not always correlate with severity of AS. Cases of severe AS often have a low intensity of murmur due to reduction of flow across the valve

- Increase murmur intensity after a PVC (post-PVC beat has a lower afterload, larger preload, and more inotropy, which increases murmur intensity in AS, and decreases/no change in MR)

Systolic ejection click may suggest bicuspid aortic valve

Associated findings

- Screening for coarctation of aorta (delayed femoral pulse, upper/lower limb BP differential, etc.)

JAMA Rational Clinical Exam

Investigations

ECG: LVH findings are common as a result of adaptation to LV pressure overload.

Chest x-ray: CXR may show a calcified aortic valve and aorta, along with features of heart failure (cardiomegaly, pulmonary edema, etc.)

Echocardiography: TTE is the preferred test for diagnosis and is recommended in any patient with signs or symptoms suggestive of aortic stenosis or bicuspid aortic valve.

TTE allows for the determination of:

Aortic valve anatomy

Etiology of AS

Associated aortopathy

Hemodynamic consequences (aortic pressure gradient and velocity)

LV size and systolic function

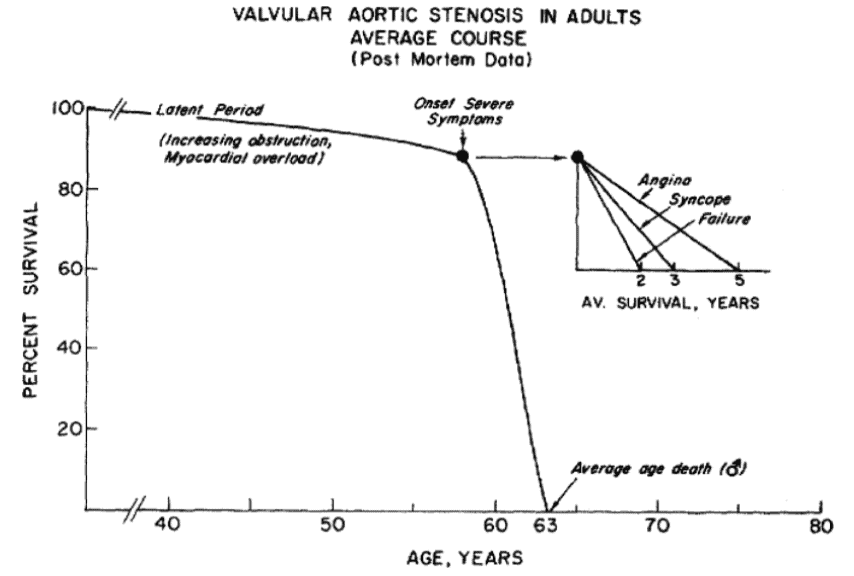

Severe Aortic Stenosis: Aortic Peak Velocity ≥4 m/s or mean gradient ≥40 mm Hg (AVA typically ≤1.0 cm2 but not necessary for diagnosis)

NOTE: Physical exam is crucial in aortic stenosis assessment. Echocardiogram requires skill and experience to find the highest gradients of the jet. An inexperienced echocardiographer or sonographer can miss the gradient by mis-aligning the probe with the direction of the jet.

If your physical exam suggests severe AS, and is discordant from the severity on echocardiogram, you must repeat the echocardiogram!

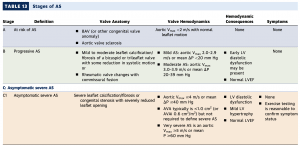

Aortic Sclerosis | Mild AS | Moderate AS | Severe AS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Aortic jet velocity (m/s) | < 2.5 | 2.6 – 2.9 | 3.0 – 4.0 | > 4.0 |

Mean gradient (mmHg) | < 20 | 20 – 40 | > 40 | |

Aortic valve area (cm2) | > 1.5 | 1.0-1.5 | < 1.0 |

NOTE: Valve gradients and valve area are the echocardiographic assessments of severity. Valve gradient is a measured value, and is used in guidelines to assess severity. Aortic valve area is a calculated value, which has higher room for error, but can be a more accurate severity representation in LFLG-AS (see below).

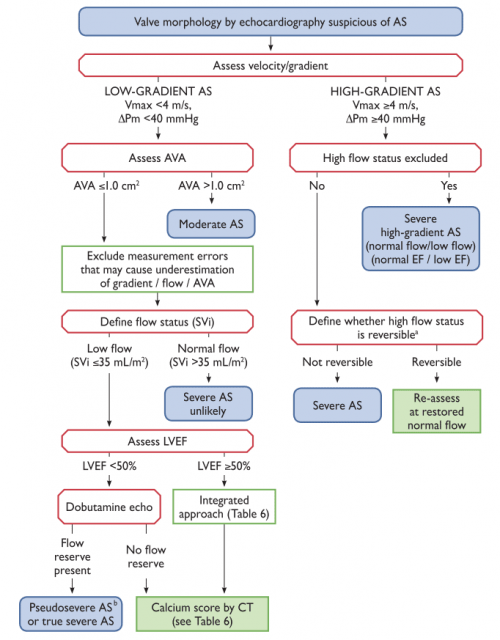

LFLG severe AS

There is a subset of patients with severe AS who have reduced flow across the aortic valve due to the inability of the LV to generate high contractile force. This leads to artificially low gradients, which can deceive physicians into underestimating the true severity of valve stenosis.

Physicians must suspect LFLG-AS if LVEF is reduced in presence of AS (or LV stroke volume index < 35 mL/m2/beat)

There are two types of LFLG Severe AS (two ways LV contractile force is reduced):

LFLG-AS with Reduced LVEF (EF < 50%)

LFLG-AS with Preserved LVEF (diastolic dysfunction)

A dobutamine stress echo (or invasive hemodynamic assessment) helps further assess severity. Dobutamine is an inotrope, which increases LV contractility allowing determination of:

Contractile reserve – whether the ventricle is able to generate higher gradients with an inotrope. Failure to increase stroke volume (>20%) on dobutamine suggests lack of contractile reserve, which is associated with poor outcomes. This does not disqualify the patient from valve intervention.

Gradient response – Assess gradient with increased stroke volume. There are two possibilities:

1. True Severe AS: Gradient increases to the severe range with no change in valve area. The previously reduced gradients were seen because the ventricle was unable to generate contractile force. When contractile force is augmented with the inotrope, the gradients increase to reveal true severe AS.

2. Pseudo-AS: Gradient remains the same or improves. Suggests valve area is small because the ventricle does not generate enough force to open the valve. With inotropy, contractile force increases, which leads to improved valve opening (larger calculated valve area and lower/unchanged gradients).

NOTE: Hypertension can lead to underestimation of gradients, and must be controlled before assessment of AS.

- Aortic Vmax ≥4 m/s or mean ΔP ≥40 mm Hg

Management

Asymptomatic AS

In asymptomatic AS, serial monitoring with echo is indicated. Timing of follow-up interval is based on severity of AS:

| Mild AS | Moderate AS | Severe AS (asymptomatic) |

| Echo q3-5 years | Echo q1-2 years | Echo q6months – 1 year |

Exercise stress testing is recommended to confirm the absence of symptoms and assess for high risk features (see below).

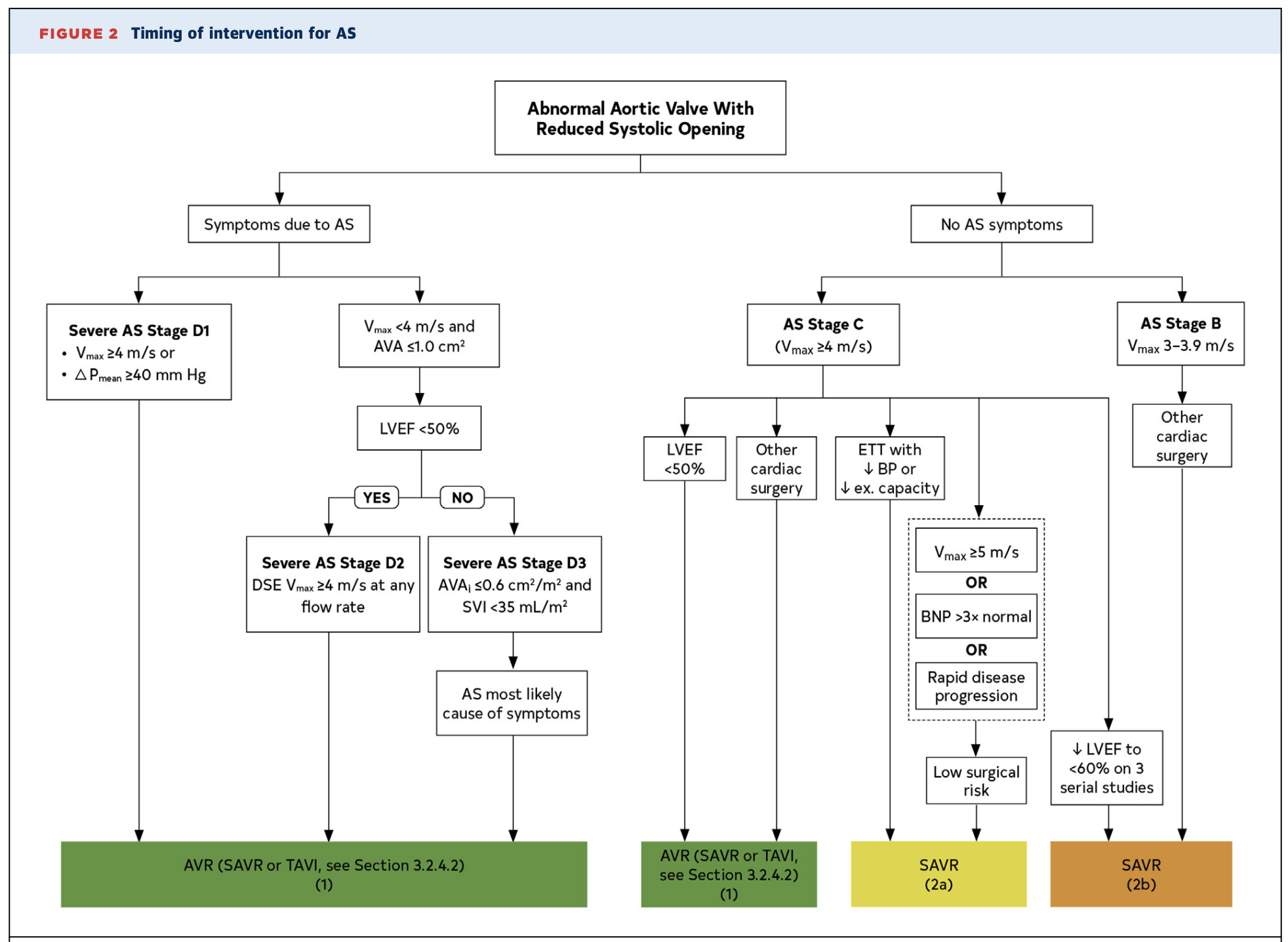

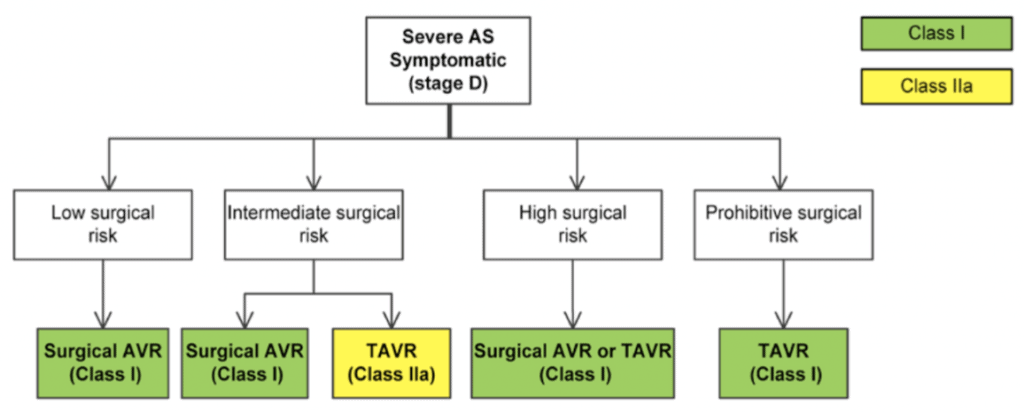

Symptomatic severe AS

For severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, management is surgical or interventional.

- Medical Management

- Only temporizes symptoms – the mainstay in management of AS is interventional.

- Diuretics – can help with symptomatic pulmonary edema.

- Hypertension Management

- In patients with symptomatic severe AS, afterload-reducing agents such as ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and nitrates must be avoided. Hypotension associated with medical therapy can be life threatening.

- Patients with asymptomatic AS (AHA Stage A-C) can be treated for hypertension with caution.

- Statins – Initial retrospective studies had positive results, but later prospective studies found statins do not affect outcomes in AS.

- Valve Intervention

- Specialist medicine physicians must know indications for valve intervention in patients with severe aortic stenosis.

| Indications for Aortic Valve Replacement |

|---|

| AHA 2020 Valve Guidelines |

|

Choice of aortic valve prosthesis

Choice of bioprosthetic versus mechanical should account for valve durability, potential need for anticoagulation, and patient preferences.

In general, mechanical valves are very long-lasting but come with the need for lifelong anticoagulation with warfarin. Bioprosthetic valves do not generally require anticoagulation but come with a high risk for early valve deterioration.

The AHA 2017 guideline suggests that patients < age 50 should favour mechanical AVR, unless anticoagulation is contraindicated or undesired. Patients over age 65 can typically favour bioprosthetic AVR, as the valve is likely to outlive them. Patients aged 50-65 are in a “grey area”, and decisions must be personalized.

Note that all TAVI valves are bioprosthetic. If the decision is made to implant a mechanical valve, then surgery is required. If a decision is reached to implant a bioprosthetic valve, then another decision between TAVR (TAVI) and SAVR must be made.

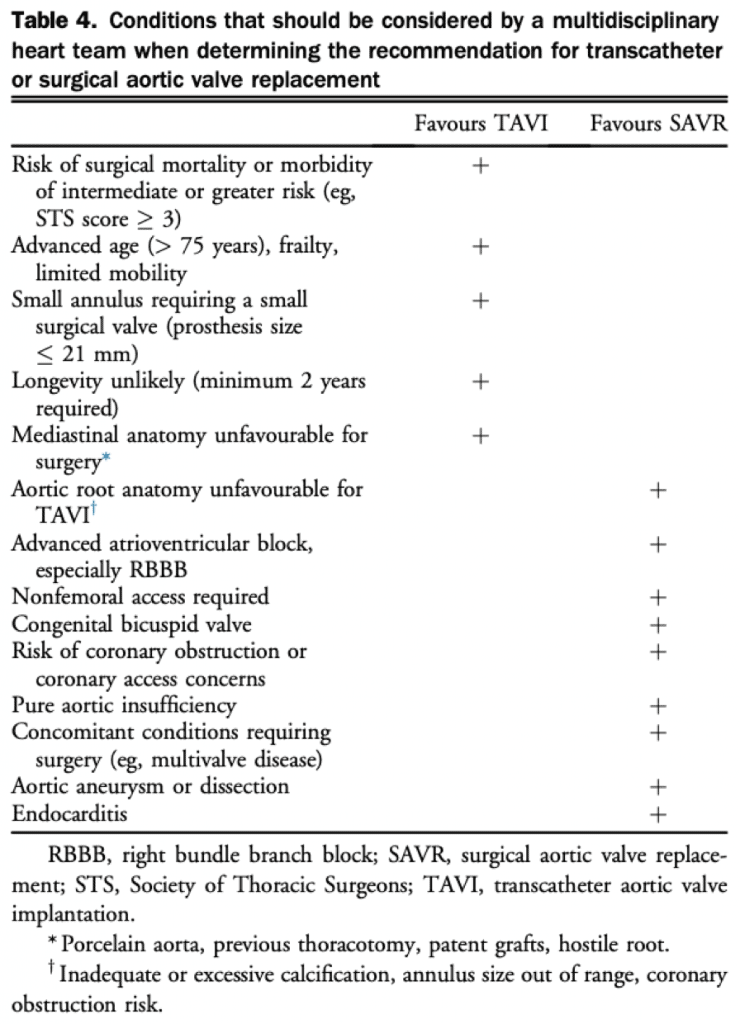

SAVR vs TAVR

The choice of TAVR vs. SAVR relies on balancing operative risks with the benefits of a mechanical surgical valve. This is usually based on the discussion between the valve multidisciplinary team and the patient. Some factors that are considered are outlined in the figure to the right.

NOTE: Surgical risk is determined with STS Score, but EuroScore has also been used.

- > 8% is high

- 3-8% is intermediate

- < 3% is low

- (PARTNER trials used ≥4 as cutoff; also in ESC Guidelines)

NOTE: TAVR has not been validated for bicuspid valve, and surgical approach remains the standard.

Authors

- Primary Author: Dr. Matthew Church (MD, FRCPC, Cardiology Fellow), Dr. Pavel Antiperovitch (MD, FRCPC, Cardiologist)

- Reviewer: Dr. Atul Jaidka (MD, FRCPC, Cardiology Fellow)

- Copy Editor: Megha Shetty (MD Candidate)

- Last Updated: February 20, 2021

- Comments or questions please email feedback@cardioguide.ca